CLARA BRIM

CLARA BRIM, enslave by William Lyons of Branch, Louisiana, now lives in Beaumont, Texas.

The town of Branch was known in slave days as Plaquemine Bouley.

Clara estimates her age to be 100 or 102, and from various facts known to her and her family,

this would seem to be correct.

“Old massa’s name was William Lyons.

I didn’t have no old missus, ’cause he was a bachelor.

He had a big plantation.

I don’t know how big but dey somethin’ like twenty fam’lies of slaves and some dem fam’lies had plenty in dem.

My ma was Becky Brim and pa, he name Louis Brim.

She come from Old Virginny.

Dey work in de field.

I had two sister name Cass and Donnie and a brudder name Washington.

He went off to de war.

When it break out dey come and take him off to work in de army.

He lost in dat war.

He didn’t come back.

Nobody ever know what happen to him.

“Some de houses log house and some plank, but dey all good.

Dey well built and had brick chimneys.

Dey houses what de wind didn’t blow in.

Us had beds, too, not dem built in de wall.

Us sho’ treat good in slavery times, yes, suh.

Old massa give us plenty clothes to keep us good and warm.

He sho’ did.

“Old massa, he wasn’t marry and eat de same things de slaves eat.

He didn’t work dem in de heat of de day.

‘Bout eleven o’clock, when dat sun git hot, he call dem out de field.

He give dem till it git kind of cool befo’ he make dem go back in de field.

He didn’t have no overseer.

He seed ’bout de plantation hisself.

He raise cotton and corn and sweet ‘taters and peas and cane, didn’t fool with rice.

He didn’t go in for oats, neither.

“When Sunday come Old Massa ask who want to go to church.

Dem what wants could ride hoss-back or walk.

Us go to de white folks church.

Dey sot in front and us sot in back.

Us had prayer meetin’, too, reg’lar every week.

One old cullud man a sort of preacher.

He de leader in ‘ligion.

“When de slaves go to work he give dem de task.

Dat so much work, so many rows cotton to chop or corn to hoe.

When dey git through dey can do what dey want.

He task dem on Monday.

Some dem git through Thursday night.

Den dey can hire out to somebody and git pay for it.

“Old Massa even git de preacher for marryin’ de slaves.

And when a slave die, he git de preacher and have Bible readin’ and prayin’.

Mostest de massas didn’t do dat-a-way.

“I as big in war time as I is now.

I used to do anything in de field what de men done.

I plow and pull fodder and pick cotton.

But de hardes’ work I ever done am since I free.

Old Massa, he didn’t work us hard, noway.

“He allus give us de pass, so dem patterrollers not cotch us.

Dey ’bout six men on hoss-back, ridin’ de roads to cotch niggers what out without de pass.

Iffen dey cotch him it am de whippin’.

But de niggers on us place was good and civ’lized folks.

Dey didn’t have no fuss.

Old Massa allus let dem have de garden and dey can raise things to eat and sell.

Sometime dey have some pig and chickens.

“I been marry his’ one time and he been dead ’bout forty-one years now.

I stay with Old Massa long time after freedom.

In 1913 I come live with my youngest girl here in Beaumont.

You see, I can’t ‘member so much.

I has lived so long my ‘memberance ain’t so good now.

...

####

… w

Susie King Taylor

Every day at 9am, Susie King Taylor and her brother would walk the half a mile to the small schoolhouse, their books

wrapped in paper to prevent the police from seeing them.

Her grandmother made sure of it – she wanted Susie to be able to read and write.

Susie was barely in her early teens when her family fled to St. Simons Island, a Union controlled area in Georgia,

during the Civil War.

With her inquisitive eyes and kind demeanor and her education, she impressed the army officers.

They asked that she become a teacher for children and even some adults.

“I would gladly do so, if I could have some books,” she replied.

And so she became the first black teacher of freed black students to work in a freely operating freedmen’s

school in Georgia.

Not long after, Susie married, and joined her husband and his regiment as they traveled.

She became their teacher, teaching the illiterate men to read and write.

It was also during this time that she became a nurse to the men, thus making her the first black army nurse

in the Civil War.

All this she accomplished before the age of 18.

Looking back on her time as a nurse, she said that “I gave my service willingly for four years and three months without

receiving a dollar.

I was glad…to care for the sick and afflicted comrades.”

####

…. w

Preely Coleman

Preely Coleman, who had been born into slavery, at the age of 85 in Tyler, 1935.

Preely was born in 1852 in New Berry, South Carolina, but he and his mother were sold and brought to Texas

when Preely was only one month old.

They settled near Alto, where Preely lived most of his life.

Here’s what he had to say, preserved in his own voice by the WPA:

“I’m Preely Coleman and I never gits tired of talking.

Yes, ma’am, it am Juneteenth, but I’m home, ’cause I’m too old now to go on them celerabrations.

Where was I born?

I knows that ‘zactly, ’cause my mammy tells me that a thousand times.

I was born down on the old Souba place, in South Carolina, ’bout ten mile from New Berry.

My mammy belonged to the Souba family, but its a fact one of the Souba boys was my pappy and so the Soubas sells my

mammy to Bob and Dan Lewis and they brung us to Texas ‘long with a big bunch of other slaves.

Mammy tells me it was a full month ‘fore they gits to Alto, their new home.

“When I was a chile I has a purty good time, ’cause there was plenty chillen on the plantation.

We had the big races.

Durin’ the war the sojers stops by on the way to Mansfield, in Louisiana, to git somethin’ to eat and stay all night, and

then’s when we had the races.

There was a mulberry tree we’d run to and we’d line up and the sojers would say,

‘Now the first one to slap that tree gits a quarter,’ and I nearly allus gits there first.

I made plenty quarters slappin’ that old mulberry tree!

“So the chillen gits into their heads to fix me, ’cause I wins all the quarters.

They throws a rope over my head and started draggin down the road, and down the hill, and I was nigh ’bout

choked to death.

My only friend was Billy and he was a-fightin’, tryin’ to git me loose.

They was goin’ to throw me in the big spring at the foot of that hill, but we meets Capt. Berryman, a white man, and he took

his knife and cut the rope from my neck and took me by the heels and soused me up and down in the spring till I come to.

They never tries to kill me any more.

“My mammy done married John Selman on the way to Texas, no cere’mony, you knows, but with her massa’s consent.

Now our masters, the Lewises, they loses their place and then the Selman’s buy me and mammy.

They pays $1,500 for my mammy and I was throwed in.

“Massa Selman has five cabins in he backyard and they’s built like half circle.

I grows big ‘nough to hoe and den to plow.

We has to be ready for the field by daylight and the conk was blowed, and massa call out, ‘All hands ready for the field.’

At 11:30 he blows the conk, what am the mussel shell, you knows, ‘gain and we eats dinner, and at 12:30 we has to be back

at work.

But massa wouldn’t ‘low no kind of work on Sunday.

“Massa Tom made us wear the shoes, ’cause they’s so many snags and stumps our feets gits sore, and they was

red russet shoes.

I’ll never forgit ’em, they was so stiff at first we could hardly stand ’em.

But Massa Tom was a good man, though he did love the dram.

He kep’ the bottle in the center of the dining table all the time and every meal he’d have the toddy.

Us slaves et out under the trees in summer and in the kitchen in winter and most gen’rally we has bread in pot liquor

or milk, but sometimes honey.

“I well ‘members when freedom come.

We was in the field and massa comes up and say, ‘You all is free as I is.

‘ There was shoutin’ and singin’ and ‘fore night us was all ‘way to freedom.”

####

...w

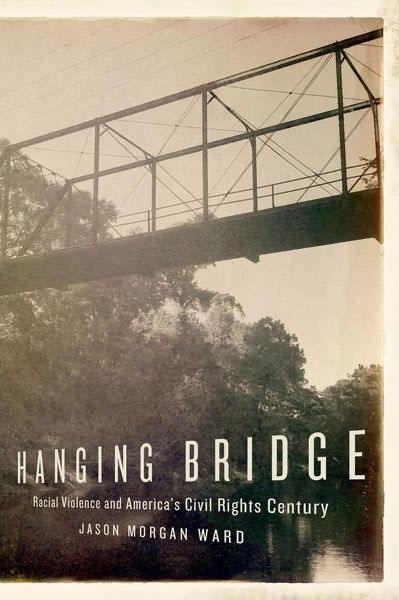

The Hanging Bridge

“In June 1966, a black civil rights worker in Clarke County, Mississippi, met a fresh recruit at the local bus station.

He loaded up John Cumbler, a white college student from Wisconsin, and took him for a ride.

He drove south toward Shubuta, a small town of seven hundred located at the southern end of the county.

Just north of town, John Otis Sumrall turned left onto a dirt road.

Pocked with puddles, the route wound past a few clusters of cabins before narrowing into a densely wooded corridor.

It seemed a road to nowhere, or at least nowhere one might want to go.

A fork in the road revealed the Chickasawhay River, and a rusty bridge.

The steel-framed span loomed thirty feet above the muddy water.

At the far end of the hundred-foot deck, the forest swallowed up a dirt road that used to lead somewhere.

Years of traffic rumbling across the bridge had worn parallel streaks into the deck, and heavy runner boards covered holes

in rotted planks.

Metal rails sagged in spots.

Still, the reddish-brown truss beams on either side stood stiff and straight, and overhead braces cast shadows

on the deck below.

On that rusty frame, between lines of vertical rivets, someone had painted a skull and crossbones and scribbled:

“Danger, This Is You.”

“This,” Sumrall announced to Cumbler, his new recruit, “is where they hang the Negroes.”

“The way he said it,” Cumbler remembered, “it could have happened a hundred years ago, or last week.”

Now closed to traffic, the Hanging Bridge still stands.

In 1918, nearly a century ago and just five weeks after Armistice Day, a white mob hanged four young blacks

—two brothers and two sisters, both pregnant—from its rails.

This was several days after their white boss turned up dead.

“People says they went down there to look at the bodies,” a local woman recalled fifty years later, “and they still see those

babies wiggling around in the bellies after those mothers was dead.”

When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—an organization less than ten years old at

the time— demanded an investigation, Mississippi governor Theodore Bilbo told them to go to hell.

Twenty-four years later, white vigilantes hanged Ernest Green and Charlie Lang—fourteen and fifteen respectively

—after a white girl accused them of attempted rape.

Newspapers nationwide ran photographs of the two boys’ corpses and that same river bridge.

“Shubuta Bridge’s Toll Stands at Six Lynch Victims,” the Chicago Defender announced.

“Some place the figure at eight,” the prominent black newspaper continued, “counting two unborn babies.”

In the wake of the latest atrocity, the Defender dispatched a black journalist to the nation’s new lynching capital.

In Meridian, a small city forty miles north, the undercover reporter asked a black taxi driver for a ride to Shubuta.

“No sir,” the cabbie replied. “I’d just as soon go to hell as to go there.”

Local whites proved just as blunt.

A white undercover investigator sent to Clarke County in November 1942 spoke with a local farmer who bragged of his

town’s most infamous landmark.

“It’s not in use anymore as a bridge,” he boasted.

“We just keep it for stringing up [n*****s].” Whites had to “mob” blacks from time to time, he explained, to keep them in line. “We had a case of that here just recently,” he added, “two fourteen-year-old boys….We put four up during the last war.”

From Jim Crow’s heyday to the earliest hints of its demise, the Shubuta bridge cast its shadow on Mississippi’s white

supremacist regime and the movement that ultimately overthrew it.

In the World War I era, on the heels of a three-decade campaign to disenfranchise and segregate African Americans across

the South, vigilantes used brutal violence to deter challenges to white supremacy.

A generation later, during World War II, local whites again relied on racial terrorism to prop up an order they claimed was

under unprecedented attack.

In both of these pivotal moments, national attention and protest politics collided at a lonely river bridge, where the

pervasive violence of the twentieth-century South rose sharply and tellingly to the surface.

The bridge boasted a history as gory as any lynching site in America, but its symbolic power outlasted the atrocities

that occurred there.

While local whites emphasized its usefulness in shoring up white supremacy, civil rights supporters recognized its

potential to galvanize protest.

After the 1942 lynchings, a black journalist branded the bridge a “monument to ‘Judge Lynch.’” The “rickety old span,”

Walter Atkins argued, “is a symbol of the South as much as magnolia blossoms or mint julep colonels.”

With its grim history, as well as with the myths and legends it inspired, the bridge reinforced white control and deterred

black resistance.

The structure was not just a monument but also an “altar” to white supremacy, as the journalist put it, a place

“to offer as sacrifices” anyone who threatened that power.

The river below the bridge flowed gently, yet Atkins predicted “a long overdue flood that will smash and sweep away

Shubuta bridge and all it stands for.”

A generation after the 1942 lynchings, that flood finally hit.

Civil rights workers, federal agents, and television reporters poured into the state in the mid-1960s, though the rising tide

of protests and marches did not reach everywhere.

Despite massive demonstrations in nearby places such as Meridian and Hattiesburg, Clarke County seemed left high and

dry.

Even as local activists and allies across the state challenged segregation and disenfranchisement, the Hanging Bridge still

stood as a reminder of Jim Crow’s past and violent potential.

Few civil rights workers ever set foot in Clarke County.

The Mississippi movement’s high-water mark—1964’s Freedom Summer—came and went with no Freedom Schools and no

marches in Shubuta; only a handful of the county’s black residents registered to vote.

Local people had a ready answer for anyone who wondered why the movement seemed to have passed them by.

Old-timers across the county still spoke of a bottomless “blue hole” in the snaking Chickasawhay River,

where whites had dumped black bodies.

Far more mentioned the bridge that spanned the murky water.

The myths could be just as muddy, the details dependent on the storyteller.

However the events were mythologized, a fundamental truth remained.

“Down in Clarke County,” a Meridian movement leader recalled, “they lynched so many blacks.”

A white northern journalist who visited in the wake of the 1942 lynchings predicted that the mob impulse would die hard.

“The lynching spirit means more than mob law,” he warned.

“It means the inability of so many white Southerners to keep their fists, their clubs, or their guns in their pockets when a

colored person stands up for his legal rights.”

When black activists in Clarke County defied mobs and memory in pursuit of political power and economic opportunity,

they provoked a new round of violent reprisals.

In the process, they fixed outside attention on problems that persisted in the wake of the soaring speeches and legislative

victories of the civil rights era.

In this rural corner of Mississippi previously known for lynchings, those activists used that infamous reputation to focus

national attention on ongoing battles against racial terrorism, grinding poverty, and government repression.

Their story reaches back into generations when the rural South seemed all but cut off from national campaigns against

discrimination and abuse, but grassroots activism in Clarke County also extends the story deep into the 1960s and beyond.

Racial violence—both in bursts of savagery that sent tremors far beyond Mississippi’s borders and in the everyday

brutalities that sustained and outlived Jim Crow—connects the generations and geographies of

America’s civil rights century.

In reclaiming these stories, we bridge the gap between ourselves and a past less distant than many care to admit.

To acknowledge the role of violence in shaping our racial past is no guarantee that we can face honestly the ways in which it

informs our racial present, but it is a place to start.

In the history of lynching, place is often difficult to pin down with precision—hanging trees long since felled,

killing fields reclaimed by nature, rivers and bayous that hide the dead.

Yet one of America’s most evocative and bloodstained lynching sites still spans a muddy river, and it still casts a shadow.

https://time.com/…/hanging-bridge-excerpt-mississippi…/

####

… w

...

warm? … is anyone warm? … ???? Oh well ….

One thought on “…. Story Time …”

Comments are closed.